The Effects of industry on ecology Anu Murthy

Andrew C. Isenberg is a professor of history at Temple

University. He is also the author

of The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History and is a former

fellow of the Huntington Library

and the Shelby Cullom Davis

Center for Historical Studies.

The Californian environment has

been altered by settlers many times to meet the needs of technological

advances. The 1849 gold rush, however, has had one of the most significant

influences on California��s ecology.

Before the 1850s many Native American tribes cultivated its diverse

terrain, and California remained

virtually free of industry and technology. The gold rush changed all of this.

With the discovery of gold and the end of the Mexican War, came the American

desire to control an environment ��composed on numerous and complex interconnections��1. New mining practices

themselves caused the creation of many other industries, such as commercial

agriculture, hunting, fishing, railroads, and lumber. Bonanza farms�Xlarge

ranches dependent on industry�Xprogressed and quickly replaced older

agricultural methods. Trying to quicken the development of natural resources,

industrialists attempted to compensate for the high costs of capital and labor.

Their goal of conquering California��s

distinct ecology had various effects on the environment. Andrew C. Isenberg��s Mining

California: An Ecological History explores these

consequences and analyzes the gradual industrialization of California.

Chapter 1 of this book deals with the

effects of hydraulic mining on the environment. The few years after the

discovery of gold, settlers used laborious techniques to unearth this valuable

metal. Some of these procedures included panning, makeshift dams, and simply

digging. Before hydraulic mining, rivers posed a threat to industry. In the

spring, high waters prevented people from scouring gravel. In the summer,

streams receded and miners could not divert the water as they pleased. Dams

often collapsed and manmade reservoirs were generally unreliable. Therefore,

industry��s failure to control waterways made the economy run on credit. Banks

closed and currency depended on gold or foreign coins. Hydraulic mining, a

system that uses pressured water to wash hillsides, trap gold, and rinse away soil

and gravel, allowed miners to take charge of waterways. One of its major

consequences was the steady decline of independent prospectors. For investors,

hydraulic mining was beneficial in two ways. It greatly ��reduced the high costs

of labor in the gold country.��2 Due

to the deterioration of independent prospectors, gold country was employed by

wage laborers. Secondly, ��the hydraulic system extended a measure of human

control over the dynamic hydrology of the California

gold country.��3 The

unpredictable weather often made investors hesitant to commit money to mining

until the invention of hydraulic mining. However, miners soon learned to extend

their hegemony over waterways and, consequently, attracted investors to offset

the costs of labor and capital. Hydraulic mining also had negative effects on

the environment. The flushed debris from washed soil and gravel polluted the

waterways that led straight into the San Francisco

Bay. The debris destroyed the

spawning grounds of salmon and other food options; much of the mercury used in

hydraulic mines also found its way into rivers. This toxin poisoned available

water for humans, livestock, and fish. The California

legislature�Xnot yet organized due to the 1846 Mexican War�Xdid nothing to

counteract the destruction of the environment. In fact, legislation protected

industry��s right to discard wastes in public waterways. By the 1850s, courts

gave prospectors the privilege to enter public lands settled by farmers. Judges

regarded courts as merely ��a social tool that could promote change.��4

The machinery of hydraulic mining promoted other industries. A simple

nozzle at the end of each canvas hose, called a moniter,

resulted in an expanded iron industry. Capable of shooting water at great

speeds, moniters were kept running day and night. The

increased demand for this improved nozzle helped the iron industry profit.

Although hydraulic mining did inflate other commercial areas, its effects on

the environment were highly destructive.

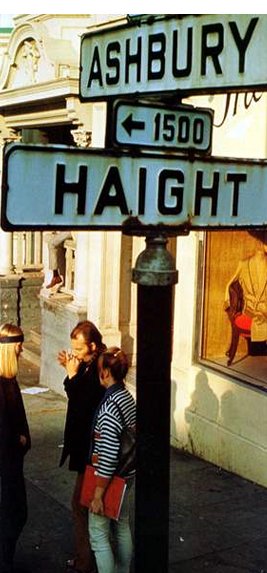

The capital of California

underwent many alterations because of the gold rush. Isenberg describes these

alterations in Chapter 2. Before gold discovery, Sacramento

contained many villages, but no cities. Substantial settlements were based on

the coast, but few metropolises existed on the interior. Most coastal towns

��served as ports and way stations for hunters who preyed on aquatic mammals.��5 Major cities were located

at the confluence of major rivers; in fact, cities operated more like

joint-stock companies than actual residential areas. Merchants and speculators

acted as investors and looked to expand their company commercially. Municipal

governments, made up of these investors, formed their board of directors. As

cities started to need better transportation, steam powered vessels and

railroads developed, and citizens became more dependent on steam. Because of

this reliance, the lumber industry also expanded. This growth, however,

destroyed Sacramento��s dense

forests and had other damaging effects on the environment. With the attraction

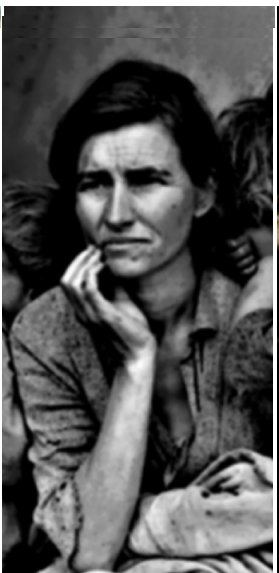

of merchandise and capital came the rise of disease. Between 1849 and 1850, a

cholera epidemic swept Sacramento.

City governments were hesitant to give resources to the poor and those without

property. The influx of diseased citizens resulted in a dirty and crowded area.

Like hydraulic mining, rapid urbanization had mostly negative effects on Sacramento.

Isenberg describes the effects of

gold discovery on the lumber industry in Chapter 3. Lumber was mainly used for

fuel and construction. It attracted many independent prospectors who looked for

employment after the expansion of hydraulics. Swept away by the excitement of a

new and rising lumber industry, loggers, like many other people, shifted the

burden of labor cost and capital on the environment. Logging techniques quickly

depleted forests and overwhelmed the market. During the mid nineteenth century,

federal legislation hoped to spur the economy by shifting public land into

private ownership. In 1878, ��the federal government accelerated the

privatization of forest lands with the passage of the Timber and Stone

Act�Kwhich opened forests on the public domain to sale for a small fee.��6 Steam power and railroads

exposed remote parts of redwood forests. The rise of technology forced loggers

to cut more trees to balance the amount of money spent on machine investment.

Like other industries, the lumber industry took its toll on the environment.

The timber in redwood belts started to decline and grasses and shrubs crowded

emerging trees out of the area. Deforestation created more river sediment which

in turn caused a sharp drop in migrating fish. The lack of canopy triggered

solar radiation and water temperatures to rise. The expansion of the lumber

industry did help the economy but as a consequence of this development, the environment

suffered.

As Isenberg starts the second half

with the decline of Californios, he shifts his study

to industry��s influence on farming. Californios, who

were married to Mexican elites, often owned large ranches on the coast that

were ideal to produce beef. Intermarriage encouraged families to cooperate in

business. Californios gained immense commercial power

from the demand for beef. However, in the 1860s, Californio

dominance receded. Three main reasons caused this decline. First, Californios were unable to adapt after the Mexican War.

Newcomers, such as Anglo-Americans had superior economic vigor and ignored the

property rights of Californios. Second, conquests of

their property reduced Mexican-Americans to segregated wage laborers. The rise

of Anglo-Americans ��destroyed the large estate owners of southern California

and led to the�Kproletarianization of Mexican-Americans.��7 Third and most important, southern California��s

environment was drought prone. Rancheros refused to adapt to an intensive stockraising system, where farmers cultivated hay and

constructed fences. Instead they clung to an extensive stockraising

system, where the herds were let over large areas. This technique left

rancheros dependent on grasslands for their livestock��s health. Many Californios were land rich and cash poor as the beef market

slumped. They were able to sustain by selling cattle hides and tallow to Britain

and the United States.

They also compensated for the lack of labor by hiring Native Americans.

However, intensive stockraising made rancheros

vulnerable to well-financed competitors. By the 1850s, the decline in the beef

market led to overgrazing. Ranchers could not sell their livestock; buyers were

not inclined to trust southern California

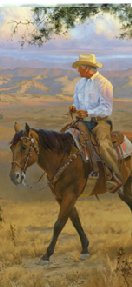

wool either. In the 1860s, cowboys, more cooperative with financers than

ranchers were, replaced Californios. Their

settlements also failed due to the 1863 drought and the 1864 grasshopper

infestation.

The fifth and last section of this

book deals with enclosure of Native American lands. In 1864, the Modoc tribe

assented to cede their California

lands and live on a reservation in Oregon.

Some Modocs stayed and worked on ranches but ranchero

opposition forced the Californian Army to drive remaining Modocs

out of California. This particular

tribe was not ignort of the Americans. They were

��highly acculturated to Euroamerican mores�K [and] they enjoyed good relations with the townspeople.��8 However, the discovery of gold

and ranch extensions pushed the Modocs farther away

from their homeland. Many tribes shifted into the wage labor market. Native

American women were often forced to become domestic servants or prostitutes.

The rise in prostitution prompted widespread sexually transmitted diseases,

which in turn caused a decline in Modoc population. Before the influx of Euroamerican settlers, the Modoc tribe dominated the

plateau. They relied on the diversity of resources and planned their lives

around the seasons. By the 1840s, however, Euroamericans

began to inhabit Oregon

territory, thereby disrupting the Modoc trade patters. The gold rush and its

new technologies proved to be serious blow to the Modoc tribe��s sustenance

strategies. In 1873, the Modoc War ended and Euroamerican

settlers gained control of the lands. They overpowered most of the Native

Americans and concluded the enclosure of the plateau.

Isenberg��s thesis states that

nineteenth-century industrialism in California

is based mainly on the struggle to control the environment. Through his

examples of how ��industrialism ultimately affected every part of California��s

environments,�� Isenberg implies that settlers�� desire for ecological

power damaged the environment as well as the settlers�� lives.9

In each chapter he begins with a description of a way

in which industry expanded during the years of the gold rush. Isenberg then

transitions into a subtle disparagement of industrialism��s pernicious effect on

California��s rich environment.

For example, Isenberg portrays the discovery of hydrology. He explains how

dominance over waterways was helpful to settlers, but he never lingers for long

on its benefits. Even though hydraulic mining seems like an efficient

technique, Isenberg focuses most of chapter on the negative effects of

hydrology on the environment. In the last section, Isenberg connects racial

discrimination of Native Americans with environmental destruction. Isenberg��s

thesis covers various areas of California

during the gold rush years, yet these subjects are all tied together by a

common message: American settlers�� fight for industrialism harmed the

environment.

Andrew C. Isenberg is a history

professor who has written copious books on America��s

environmental history. Possibly influenced by the popular discussion of global

warming and modern day environmental problems, Isenberg��s book shows how

technology has detrimental effects on the Californian ecology. Isenberg assumes

that environmental predicaments still trouble American society today. His

description of past attempts to conquer nature serve as a warning to the modern

world that damage to the environment is the same thing as damage to the

society. Isenberg hopes that modern society can learn from early settlers who

��repeatedly discovered that their alterations of nature were not without

consequence�KEuroamericans reinscribed

the political ecology of California

upon the landscape of the West.��10 Isenberg,

being a history professor and an environmentalist, knows the severe outcomes of

ecological destruction. Isenberg wants readers to avoid history��s mistakes and

not try to overpower nature. Published in 2005, Isenberg��s

book falls into Neo-Conservative historiography. Characteristic of this

category, Isenberg views the effects of the gold rush objectively. Little of

his personal opinions are present and there is no ideology. In light of recent

importance given to the planet��s ecology, Isenberg retells history so that

Americans today will realize the devastating effects of environmental

pollution.

Peter Coates, an environmental

history professor, reviewed Isenberg��s book in the Journal of American

History. Largely in praise of this work, Coates remains impressed by

Isenberg��s sole focus on Californian history. He complains that ��new western

[history] tend[s] to marginalize the state��11,

thereby stressing that Isenberg��s focus is necessary for a complete

understanding of western ecology. He compares and contrasts this work to other

historians�� pieces, implying that Isenberg��s research on the subject is

accountable. Coates also specifically comments on Isenberg��s use of the Modoc

tribe. Impressed by Isenberg��s insight, Coates commends the way the author

employs Native American relationships to show how enclosure also affected the

environment. Coates expresses his approval of Isenberg��s thesis, stating that

this book is a ��welcome addition to the growing number of studies on the

environmental history of mining in the American West.��12

Coates moves on to applaud Isenberg��s literary style.

Isenberg��s work is extremely

informative and well-written. He explains sophisticated parts of California��s

history in comprehendible language. Connecting each section of his book to

convey a common message, Isenberg does more than simply relate stories of this

state��s past. He delves deeper in his studies and carefully investigates the

many causes of California��s

environmental deterioration. The fact that Isenberg can bond various subjects,

ranging from hydrology to Native American relations, into one piece and

intertwine their implications is truly impressive. Isenberg��s constant

reference to various historians, such as J. Willard Hurst13,

a legal historian, and Leonard Pitt14,

who specializes in Californio history, reflects his

deep knowledge in the area of environmental history. The references also serve

as a change for the reader; instead of an avalanche of his own opinions,

Isenberg offers diverse points of view and analyzes the effects of California��s

industrialization.

California��s

rate of industrialization was heavily dependant on eastern United

States. Before the days of hydraulic mining,

independent prospectors struggled to attract investors from the rest of United

States and Europe.

They worried that ��investors were wary of committing capital to California

placer mining until the industry had tamed the volatile environment.��24

Because of the high costs of labor and capital, placer miners lacked

investments and had no means to contract more efficient machines. The

Industrial Revolution in the East and Midwest gradually

seeped through the country and finally reached California.

Because of the Industrial Revolution, California

started to conquer the environment, thereby gaining the trust of outside

investors. The Mexican War also had a profound effect on California.

The Californios had long dominated southern California

but the influx of Euroamerican settlers terminated

this supremacy. After the Mexican War, Americans from the East and Midwest

completely ignored the Californios�� property and

squatted on their estates. The rancheros refusal to adapt to these changes

caused the end of their agrarian lifestyle and paved the way for industry.

Although California

was influenced by happenings in the East, its events were also distinctive from

the rest of the country. Unlike the East that had distinctive regions of

industry or agriculture, California

contained both simultaneously. The diverse environment of mountains, deserts,

forests, and coastal areas allowed California

to try its success in ranches and then industry. Another difference was

individuals�� reaction to the ecology. Americans in the East took whatever the

surroundings offered, thereby creating opposite cultures centered in the North

and in the South. On the other hand, Euroamericans

who settled in California looked

to conquer the land and alter it according to their needs.

The

1849 gold rush changed California

drastically. Initially a territory of

Mexican- American cattle ranches, California

evolved into a populous state that saw the replacement of agriculture with

industry. Isenberg��s novel reveals the ecological effects that technology had

on the once diverse Californian environment. Although an industrial revolution

seemed like the correct event for a growing area, Isenberg shows how industry

had a reverse effect. New advancements not only proved to be dangerous to the

environment, but their effects on the environment hurt settlers also. Euroamericans��

battle against the environment ended as settlers realized that they must also

��set the terms for the preservation of the natural environment.��15

This lesson that Californians learned is the message that Isenberg wishes to

convey. Control of the environment does not necessarily lead to success; the

environment should be respected and used to aid society.

1. Isenberg, Andrew C. Mining California:

An Ecological History. New York:

Hill and Wang, 2005 15.

2. Isenberg, Andrew C. 24.

3. Isenberg, Andrew C. 24.

4. Isenberg, Andrew C. 33.

5. Isenberg, Andrew C. 54.

6. Isenberg, Andrew C. 81.

7. Isenberg, Andrew C. 107.

8. Isenberg, Andrew C. 134.

9. Isenberg, Andrew C. 21.

10. Isenberg, Andrew C. 177-178.

11. Coates, Peter. "Mining California:

An Ecological History." Environmental History 11(2006): 629-630.

12. Coates, Peter 630.

13. Isenberg, Andrew C. 34.

14. Isenberg, Andrew C. 104.

15. Isenberg, Andrew C. 177.